|

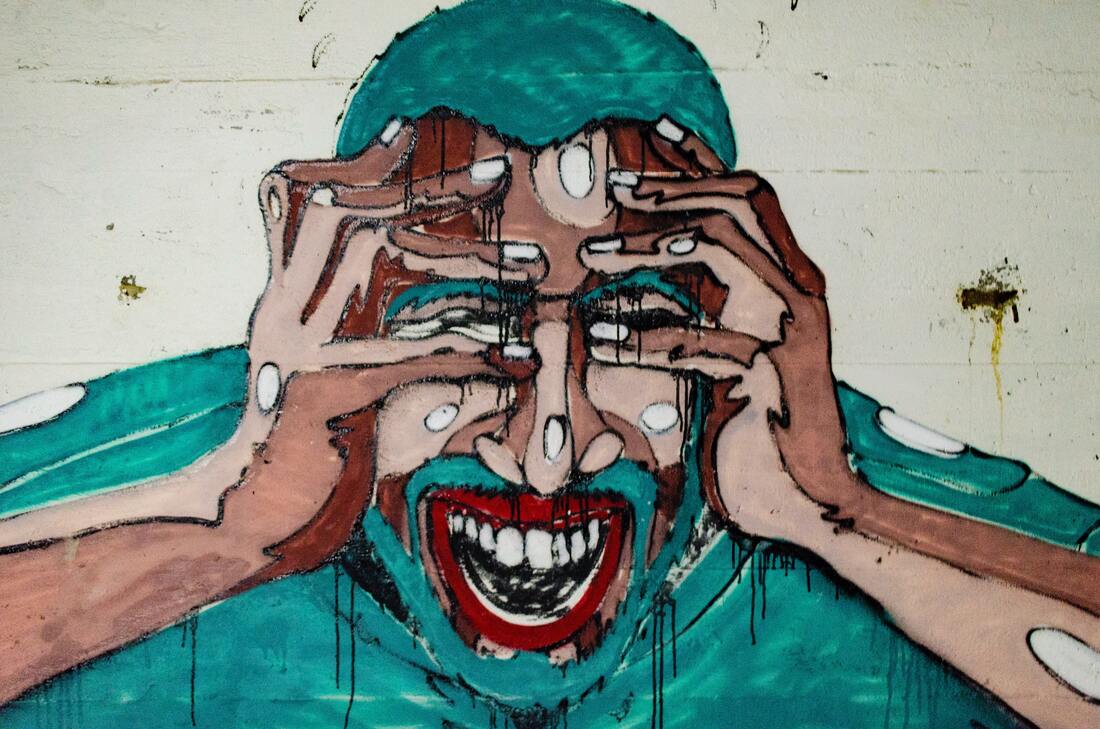

Collectively, we have long understood the relationship between stress and the gut. Reflections on this connection shows up in common phrases, like "I get butterflies in my stomach when I'm nervous," and "I just felt me stomach drop with dread." Emotional strain can trigger digestive upset and has been shown to play a role in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the onset of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and intestinal permeability (aka "leaky gut syndrome"). This relationship goes both ways: imbalances in the gut can trigger mood and cognitive imbalances too, including depression and Alzheimer's disease.

The connection between the gut and the brain/heart is complex, so I'll be adding to a collection of blogs on the topic over the coming months. Click on "The Mind-Gut-Heart Connection" category to learn more. We'll start the conversation at the end of the digestive tract - in the colon - with the ever-amazing microbiota. There are bacteria and yeast living in and on your body. That's a good thing. I sometimes joke that we need to look no further than these microorganisms sharing our bodies for the meaning of life: our purpose is simply to play host. Make them comfortable and well-fed. If we do that, we've got a good start on a good life. When our microbiome is healthy and robust, those bugs make nutrients for us, like short chain fatty acids and vitamins. They transform compounds in our food, like fiber and phytonutrients, into useful forms. They maintain our colonic environment and help us maintain digestive health. They communicate with and enhance our immune systems, and help us prevent disease. They even make neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine to facilitate positive thoughts and balanced emotions. So playing the role of a gracious host really does go a long way on our wellness journey! The most accurate term for these bacteria and yeast living in and on our body is "microbiota," a term used interchangeably with "microbiome," though they are distinct words. "Microbiota" refers to the microorganisms found in an environment, while "microbiome" actually describes the collection of genetic material from said microorganisms. I might use these words interchangeably because "microbiome" is more commonly used and I think it's more important to see the big picture than get caught in the weeds. On the human body, there are microbiota found in the sinuses, respiratory tract and lungs, the mouth, the skin, and the digestive tract. The most heavily populated microbiota is found in the colon. In and on the human body, there are 10 times more microbiota cells then there are cells of human origin. In other words, there are ~150 times as many genes coming from microorganisms than from the human genome. (Learn more about the microbiota in Dr. Barrett's blog article here.) Stressful encounters change the microbiota...and the microbiota changes the stress experience. Stressful experiences early in life inform the composition of the microbiota by impacting the type and abundance of microorganisms that colonize the colon. It is estimated that the microbiota is established by age three, so these early childhood experiences can have a lifelong impact on an individual's microbiota. At all stages of life, beneficial microorganisms like Lactobacillus sp. decline in the presence of stress - even short-term stress. Lactobacillus is a genus of bacteria that is well-studied and easily found in over-the-counter probiotic supplements and fermented foods like yogurt. It's an important "bug" for many reasons, one of which is that it reduces inflammation in not just the digestive tract, but throughout the body. Repeated exposure to stressors has an exponential impact on Lactobacillus species and other beneficial microorganisms in the microbiota, giving us another reason to reduce stress and build resilience. Interestingly, the composition of the microbiota also impacts how a person responds to stress. Potentially pathogenic microorganisms, like E. coli, can trigger a heightened stress response. Similarly, a microbiota that is not diverse or abundant in beneficial microorganisms can also heighten the stress response. In other words, stress impairs the health of the microbiota. And a sick microbiota exacerbates the harmful impact of stress. Addressing gut health - including the health of the microbiota - is a necessary component of any functional nutrition plan. This becomes all the more important when lifestyle factors like stress and resilience (the ability to recover from stressful experiences) are indicated in the root cause of symptoms. Incorporating ferments, fibers, therapeutic probiotic therapy and nutrients that enhance the ecosystem of the colon may all be recommended to balance HPA axis imbalance, support recovery from burnout and enhance resilience. References:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

I love food.I love thinking about it, talking about it, writing about it. I love growing food, cooking and eating food. I use this space to try to convey that. Follow me on social media for more day-to-day inspiration on these topics. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed