|

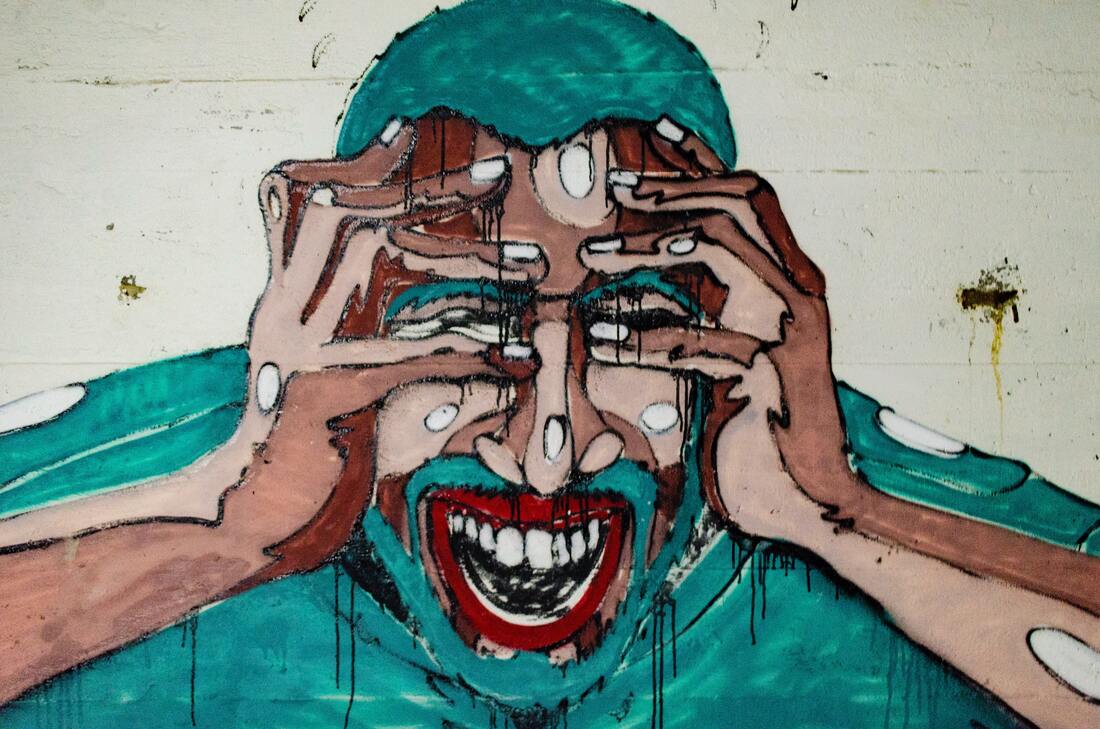

Collectively, we have long understood the relationship between stress and the gut. Reflections on this connection shows up in common phrases, like "I get butterflies in my stomach when I'm nervous," and "I just felt me stomach drop with dread." Emotional strain can trigger digestive upset and has been shown to play a role in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the onset of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and intestinal permeability (aka "leaky gut syndrome"). This relationship goes both ways: imbalances in the gut can trigger mood and cognitive imbalances too, including depression and Alzheimer's disease.

The connection between the gut and the brain/heart is complex, so I'll be adding to a collection of blogs on the topic over the coming months. Click on "The Mind-Gut-Heart Connection" category to learn more. We'll start the conversation at the end of the digestive tract - in the colon - with the ever-amazing microbiota. There are bacteria and yeast living in and on your body. That's a good thing. I sometimes joke that we need to look no further than these microorganisms sharing our bodies for the meaning of life: our purpose is simply to play host. Make them comfortable and well-fed. If we do that, we've got a good start on a good life. When our microbiome is healthy and robust, those bugs make nutrients for us, like short chain fatty acids and vitamins. They transform compounds in our food, like fiber and phytonutrients, into useful forms. They maintain our colonic environment and help us maintain digestive health. They communicate with and enhance our immune systems, and help us prevent disease. They even make neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine to facilitate positive thoughts and balanced emotions. So playing the role of a gracious host really does go a long way on our wellness journey! The most accurate term for these bacteria and yeast living in and on our body is "microbiota," a term used interchangeably with "microbiome," though they are distinct words. "Microbiota" refers to the microorganisms found in an environment, while "microbiome" actually describes the collection of genetic material from said microorganisms. I might use these words interchangeably because "microbiome" is more commonly used and I think it's more important to see the big picture than get caught in the weeds. On the human body, there are microbiota found in the sinuses, respiratory tract and lungs, the mouth, the skin, and the digestive tract. The most heavily populated microbiota is found in the colon. In and on the human body, there are 10 times more microbiota cells then there are cells of human origin. In other words, there are ~150 times as many genes coming from microorganisms than from the human genome. (Learn more about the microbiota in Dr. Barrett's blog article here.) Stressful encounters change the microbiota...and the microbiota changes the stress experience. Stressful experiences early in life inform the composition of the microbiota by impacting the type and abundance of microorganisms that colonize the colon. It is estimated that the microbiota is established by age three, so these early childhood experiences can have a lifelong impact on an individual's microbiota. At all stages of life, beneficial microorganisms like Lactobacillus sp. decline in the presence of stress - even short-term stress. Lactobacillus is a genus of bacteria that is well-studied and easily found in over-the-counter probiotic supplements and fermented foods like yogurt. It's an important "bug" for many reasons, one of which is that it reduces inflammation in not just the digestive tract, but throughout the body. Repeated exposure to stressors has an exponential impact on Lactobacillus species and other beneficial microorganisms in the microbiota, giving us another reason to reduce stress and build resilience. Interestingly, the composition of the microbiota also impacts how a person responds to stress. Potentially pathogenic microorganisms, like E. coli, can trigger a heightened stress response. Similarly, a microbiota that is not diverse or abundant in beneficial microorganisms can also heighten the stress response. In other words, stress impairs the health of the microbiota. And a sick microbiota exacerbates the harmful impact of stress. Addressing gut health - including the health of the microbiota - is a necessary component of any functional nutrition plan. This becomes all the more important when lifestyle factors like stress and resilience (the ability to recover from stressful experiences) are indicated in the root cause of symptoms. Incorporating ferments, fibers, therapeutic probiotic therapy and nutrients that enhance the ecosystem of the colon may all be recommended to balance HPA axis imbalance, support recovery from burnout and enhance resilience. References:

0 Comments

Mental health is not relegated to the brain. In fact, the digestive tract - especially the colon - play a key role in the production and reception of neurotransmitters, which is one of the reasons the gut has been called our 2nd brain. More specifically, the "2nd brain" is the ecosystem of microorganisms (the microbiota) taking up residency in the colon. To learn more about the microbiota read my long-time collaborator, Dr. Barrett's blog titled Microbiome and my previously published blog, This is Your Microbiota on Stress.

One way that the microbiome communicates with the brain is by stimulating the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve travels down the brain stem into the spinal column, innervates the abdomen and then spreads out to create a web-like cage for the digestive tract. Microbes in the colon ”tickle” the vagus nerve to communicate directly with the brain, stimulating production and secretion of neurotransmitters that contribute directly to mental wellness, including serotonin, dopamine and others. Additionally, the microbiota play a significant role in what kind of signaling molecules are produced in the gut that then communicate with the brain. The microbiota also impacts a part of the brain called the amygdala. The amygdala "...is commonly thought to form the core of a neural system for processing fearful and threatening stimuli, including detection of threat and activation of appropriate fear-related behaviors in response to threatening or dangerous stimuli." The composition of the microbiota - both the overall population and the diversity of the ecosystem - impacts how the amygdala develops a response to stressful stimuli and the extent to which anxiety manifests in an individual. In this way, microbiota modification via diet, lifestyle and therapeutic probiotic supplements holds promise for mental health. Another way in which the health of the microbiota contributes to the health of the mind/heart is via maintenance of the structural integrity of the digestive tract. In addition to beneficial microbes like species of lactobacillus and bifidobacteria, we also host strains of streptococcus and staphylococcus, candida and other yeasts. These potentially pathogenic microbes make toxic compounds called lipopolysaccharides (aka endotoxins). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) dismantle the harmony not just in the colon but in the small intestine too. When the microbiota is imbalanced and the potentially pathogenic microbes gain a stronghold, over time the accumulation of LPS in the digestive tract can cause intestinal permeability or "leaky gut syndrome." In a leaky gut, the barrier of the small intestine is inflamed and compromised to the extent that nutrients are not absorbed and larger molecules escape the digestive tract intact, causing inflammation throughout the body. With leaky gut we are posed with two factors contributing to mental wellness:

Here are a couple action steps you can take now for your gut - and mental - health:

These recommendations are not going to be appropriate for everyone, so it's always a good idea to consult a health care provider to get an individualized wellness plan. References

Stress and the desire to eat have a complex and interesting relationship. Some people have strong cravings and an increased appetite under stress, while others lose their appetite and motivation to eat when stressed. What makes one person eat and another not eat under stress is not clearcut, but many chemicals in the body play a role.

Hormones produced and secreted in response to psychological stressors influence appetite and the drive to satiate that hunger. Epinephrine and corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) are hormones that are released from the adrenals and hypothalamus (respectively) when we first encounter a stressor. They have an inhibitory effect on appetite (in other words, they suppress appetite). The role of these two hormones is to fuel up muscles so we can fight or flee from the (presumably life threatening) stressor. So this inhibitory effect makes sense: your body doesn't want you to pause for a snack when you should be running from the bear. (Smart body!) In an ideal world, the stressor gets handled and removed. You process the stress and your body/mind/heart returns to a balanced state (aka eustress) and you go about your business. Your appetite returns to normal, signaling appropriate times to eat and not eat. Now, if that stressor is persistent, a second wave of hormones is secreted. This time it's our buddy cortisol (released by the adrenal glands). In periods of prolonged stress, cortisol does the opposite of its first-wave compatriots - it increases appetite. Cortisol also is a hormonal motivator, so not only is your appetite stronger but your desire to eat is also increased with chronic stress. This shift is presumably protective, because no one can put up a good fight or run any distance at full speed for long without refueling. These three "stress hormones" are really important players in the adaptive nature of our stress response. They have historically done a really great job at keeping us alive in the face of imminent perils. (Thanks, guys!) When we put ourselves in a modern day example - say a global pandemic - many of us are likely experiencing persistent stress, living in a cortisol bath that drives us to the pantry to soothe our worries day after day. In terms of the relationship between stress and appetite (and the drive to satisfy it with chips and guac), there's more at play. Ghrelin is often talked about a the "hunger hormone" because when secreted by the stomach it tells the brain to find something to eat. Ghrelin also plays a role in taste perception, reward behavior and reward recognition, among other things. It also has an anti-depressant effect, which may help balance out the emotional strain of stressful experiences. Epinephrine triggers the release of ghrelin as part of that first wave response to a stressor. Again, this is a highly adaptive response that gave our ancestors the drive to refuel after they got away from the bear. For us modern day folk, who are experiencing more psychological stress than life-threatening stress (the body can't tell the difference so the hormonal response is the same), our primary response is constantly being triggered. Epinephrine goes up in response to being stuck in traffic/dealing with an argumentative co-worker/navigating a distance-learning school year with your kid(s) while working from home...and ghrelin responds in full. Dopamine has two big effects on the body in regards to stress eating. It makes us feel both rewarded (I did a thing!) and connected (My heart is soothed because I did the thing!). Even thinking about food stimulates dopamine's release in the brain, an effect that is further amplified by eating a tasty treat. The bigger the "reward" the bigger the dopamine bath, so you get bonus points for cupcakes and popcorn. Here's another cool/not cool thing about dopamine: it's adaptive. So one cupcake today is going to stimulate a dollop of dopamine that you'll need two cupcakes tomorrow to obtain. To wrap this biology lesson up and put a bow on it, here's a summary of everything above: When you encounter a stressor, whether it be life-threatening or not, it stimulates hormones that have a snowball effect that results in an increased appetite and motivation to eat. Eating relieves stress by inducing an anti-depressant effect on your body, making you feel accomplished and connected. At this point you might be thinking, "but my friend/kid/partner has the opposite experience when stressed. They lose their appetite and motivation to eat!" Everyone responds to stressors differently. Some people find it easier to return to eustress than others. Some people experience acute stressors over and over and over, but stay out of chronic stress. Some people live in chronic stress for prolonged periods of time. Additionally, dopamine receptors are more sensitive in some individuals than others, making the reward-seeking behavior (like emotional eating) more powerful. To quote my current fan-girl obsession, Emily Nagoski, PhD "we're all made of the same parts, just arranged differently." This is what makes us interesting and unique, and what makes personalized medicine and nutrition such important tools for understanding ourselves and caring for ourselves in loving and authentic ways. Understanding the mechanisms that drive behavior help me understand myself better. I hope you find the same to be true and that this article gives you some objectivity for a topic that is often loaded with self-judgment. Here's the truth: you are not bad/weak/a failure because you stress eat (or don't). Instead, you are sensitive to a chemical storm inside you that rages every time your stress response is activated. You may be tempted to go on a diet or blame your eating habits for this. But if you are looking for the root cause of stress or emotional eating, it is the difficulty of returning to eustress. Developing your stress resilience is the key to changing that pattern. Without that, your body will seek out the easiest form of relief: more food. There are several self-care practices you can use to get out of acute and chronic stress to return to eustress more effectively. Emily Nagoski, PhD and Amelia Nagoski, DMA write about this and ways to "complete the stress cycle" in their book Burnout, which Dr. Barrett and I recommend to our patients often. Read it! In the meantime, come back to this article as often as you need to to get some emotional distance from what you are experiencing. Use this information as a mindfulness bell to practice non-judgment. That awareness will serve you when you are looking for relief in food and give you the perspective of knowing yourself better so you can care for yourself better. Resources and Recommended Reading: How stress can make us overeat. Harvard Health Chuang, Jen-Chieh, Zigman, Jeffrey M. (2010). Ghrelin's Roles in Stress, Mood and Anxiety Regulation. Hindawi. No act of kindness no matter how small is ever wasted. - Aesop Last spring, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the USA and the city of Minneapolis was on shelter-in-place orders, I started taking a course called "The Science of Well-Being" taught by Dr. Laurie Santos at Yale University. Dr. Santos designed this course for her students who were exhibiting symptoms of stress and unhappiness. She focused the curriculum on research showing beliefs and practices that get in the way of or promote happiness with the goal of arming her students with practices they can use to shift their experience as "Yalies." Although I was not/am not a Yalie, I found the course to be a really sweet thing to do for myself at a time when there was so much uncertainty.

Dr. Santos provided further evidence to the strength of the mind: how our mindsets create our reality. She covered everything from meditation and gratitude journaling, to shifting mindsets about measuring accomplishments and success; spending time in nature, sleep and exercise. After the 12-week course, you know what stood out to me the most? The most effective way to increase personal happiness is being kind to others. Kindness promotes gratitude, empathy and compassion. These feelings help us feel connected with others, less alone. It reminds us that we're not so different after all, but reminds us about the core values that unite us in community with each other. Acts of kindness also move us out of selfish ego and into compassion for others. It relieves stress, boosts our immune systems and reduces anger, anxiety and depression. "Feel good" chemicals are also released in our brains, including dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin. Pain is even reduced by kindness when endogenous opioids are secreted. Doesn't that just sound like magic?! What I love about this method of mind-body medicine is that there's also a return on investment. Kindness spreads - as evidenced by pay-it-forward lines that last days - and comes back to the giver. Acts of kindness do not need to be extravagant or expensive. They could be as simple as letting someone slide into traffic or sending a "thinking of you" card to a loved one. Kindness and compassion are two things this world could always use more of, but especially now as we're rolling into year two of this global pandemic, and needing to continue staying socially and physically distanced. If this is resonating with you, start with yourself. Self-compassion (kindness aimed at yourself) is a way to relate to yourself that shows support and nurturing. We're culturally encouraged to be self-critical, so if being kind to yourself is a new way of being check out these exercises for getting a self-compassion practice started from researcher Kristen Neff, PhD. If you're trying to cultivate a new health habit, self-compassion will increase your perseverance more than criticism, so this is an important skill! It may feel easier to share kindness with the people in your life. Try integrating a small act of kindness into every day and give yourself the opportunity to observe what happens in your own mental and emotional headspace in response to the experience. References: Why Random Acts of Kindness Matter to Your Well-Being |

I love food.I love thinking about it, talking about it, writing about it. I love growing food, cooking and eating food. I use this space to try to convey that. Follow me on social media for more day-to-day inspiration on these topics. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed